- The new Section 33A may serve the interests of bankrupts, but it does so at the unjust expense of creditors, many of whom suffer equally under the burden of unpaid debts. Justice, in insolvency law, demands fairness on both sides—debtor and creditor alike.

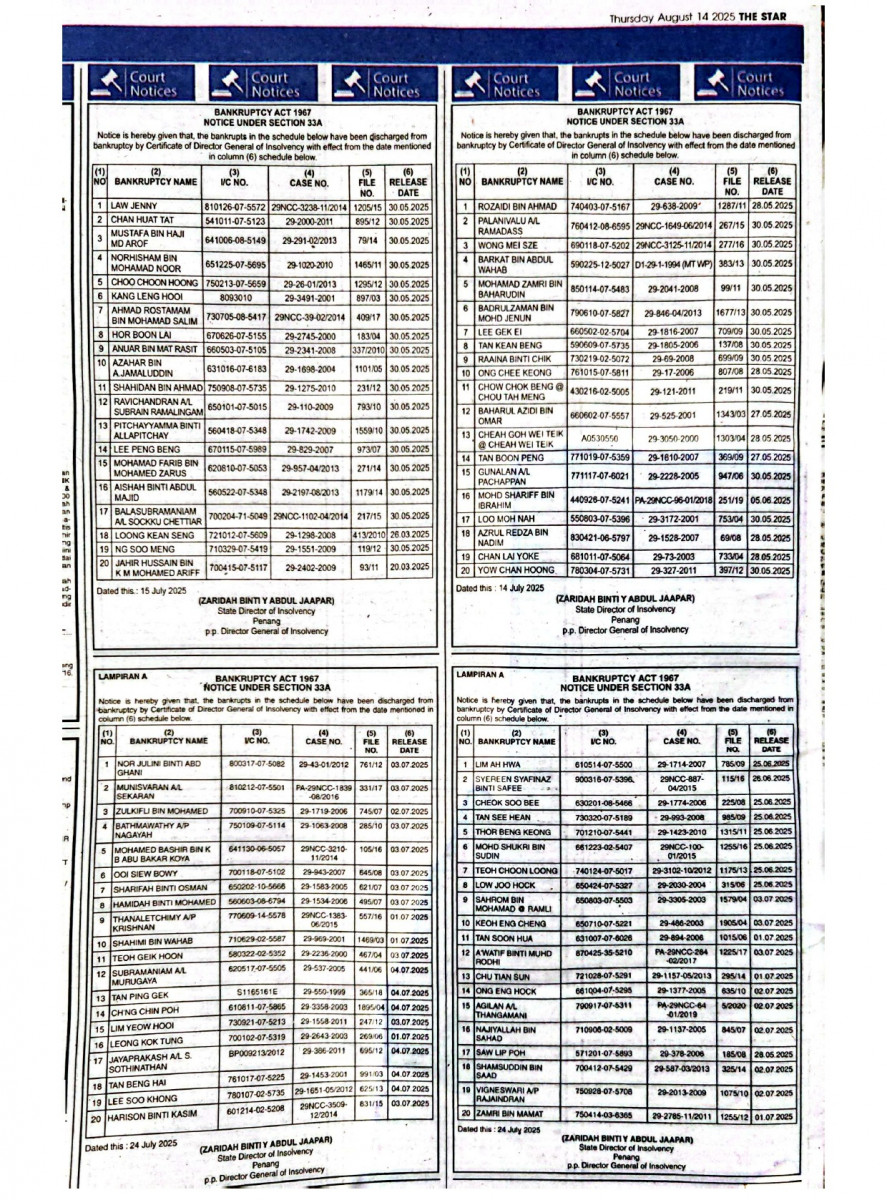

The enactment of Section 33A of the Insolvency Act 1967 via the Insolvency (Amendment) Act 2023 marked a noteworthy transformation in Malaysia’s insolvency regime. This newly introduced provision empowers the Director General of Insolvency (DGI) to issue a Certificate of Discharge (COD) to a bankrupt who has been under bankruptcy for at least five years, subject to meeting the criteria specified under the Act and regulations.

The issuance of the COD has the legal effect of discharging the bankrupt from all debts provable in bankruptcy, thereby releasing a bankrupt from the legal consequences of bankruptcy—even when no repayment has been made to creditors.

While touted as a mechanism to reduce the stigma and lifelong hardship of bankruptcy, this provision strikes a harsh blow to the very foundation of creditor protection and commercial justice.

This article argues that, while Section 33A may have been motivated by humanitarian, administrative objectives or allegedly “second chance of life”, its current framework unduly compromises creditors' rights and undermines foundational principles of insolvency law.

1. Statutory context and legal effect

Unlike a Court-ordered discharge under Section 33(3), which allows judicial oversight and creditor participation, Section 33A introduces a non-judicial administrative discharge process that can be exercised unilaterally by the DGI.

2. Erosion of creditor rights

Traditionally, insolvency law has sought to balance the interests of debtors and creditors. While recognising the need to rehabilitate the financially distressed, the regime has always included safeguards to protect creditor expectations, particularly the expectation of at least partial repayment or asset recovery.

However, under Section 33A, creditors may receive no notice of meeting, no hearings, no dividend and no recovery; yet see the bankrupt legally discharged. This departs from prior principles that viewed bankruptcy as both remedial and punitive, aimed at collective satisfaction of debts from the debtor’s estate.

Such a provision effectively extinguishes creditors’ rights without procedural justice—a troubling proposition in any rule-of-law framework.

Bankruptcy proceedings are traditionally a last resort—a legal recognition that, despite best efforts, a debtor is unable to pay. However, creditors had at least one assurance: that the law would prioritise recovery of debts from any available asset pool, and that the bankrupt would remain under restrictions until reasonable repayment was made.

Unfortunately, Section 33A has disrupted this balance. Now, creditors may receive absolutely nothing, while the bankrupt resumes life with a clean slate. This is tantamount to legalised write-offs with no restitution —a unilateral forgiveness that creditors never agreed to.

In Mayban Finance Bhd vs Lee Kee San (2014)10 CLJ 543, the Court held:

“… since the application for discharge was made by the DGI and not the bankrupt, the former bore the burden to justify that the discharge was warranty. A delicate balance between the interest of the bankrupt to free himself from the chains of bankruptcy and the rights of the Judgment Creditor, including his other creditors, to receive the judgment sum must be achieved.”

3. Policy implications and risk of abuse

Section 33A risks introducing a moral hazard and compromising commercial morality. A debtor may be incentivised to:

- Undertake excessive or reckless borrowings

- Transfer assets beyond the reach of the DGI

- Defraud judgment creditors from realising the fruit of their successful litigation

- Conceal or remove any part of the property prior to committing the “act of bankruptcy”

- Cooperate minimally with the insolvency process

- Go into hiding and avoid attendance at meetings called by the DGI

- Play ignorant when receiving notices from the DGI

- And await administrative discharge after five years

The absence of any mandatory repayment threshold or judicial scrutiny makes the discharge process vulnerable to abuse, especially by high-net-worth individuals or corporate actors using proxies.

Worse, this provision may create a perverse incentive: savvy individuals may structure their affairs to fall within the eligibility of Section 33A and benefit from a “clean exit”—at the creditors' expense.

4. Undermining commercial certainty

Further, this undermines commercial certainty. Creditors, especially unsecured lenders, suppliers, and small medium enterprises (SMEs) may reduce credit offerings or tighten lending standards in anticipation of non-recoverable defaults.

In the case of Lim Hun Seng vs Malaysia British Assurance Bhd & Ors Appeals (2010) 8 CLJ 680, Justice Ramly JCA (as he then was) said:

“The public as well as commercial players should not be imbued with the perception that a person can easily borrow money (even in big amounts) from financial institutions or create debts with other business creditors, then stash the money away, whether in his own name or any other persons and need not be repaid; then … and after the discharge he can enjoy a luxury life. If this practice and perception is not checked, the commercial morality would decline. In this type of fiasco, the Court and the DGI should be blamed for not carrying out their duties effectively under the bankruptcy law.”

5. Comparative insight: jurisdictional practices

In Singapore, under the Bankruptcy Act (now subsumed under the Insolvency, Restructuring and Dissolution Act 2018), a bankrupt may be discharged by the Official Assignee, but only after satisfying minimum contribution criteria, with creditor objections considered.

In the UK, the Insolvency Act 1986 provides for automatic discharge after 12 months but retains mechanisms for Income Payment Orders (IPOs), which require ongoing contributions from post-discharge earnings.

Malaysia’s Section 33A, by comparison, provides no continuing financial obligation and offers minimal procedural protection to creditors.

6. Landmark case

On March 12, a case was filed by a judgment creditor at the High Court to challenge Section 33A, and against the issuance of COD of a bankrupt, which was invoked unilaterally by the DGI then. The judgment creditor claimed that the DGI had failed and neglected to carry out proper and complete investigation into the affairs of the bankrupt.

In response, the DGI stated in his court affidavit that inter-alia:

- The case had been administered for 13 years and the DGI would pay dividends if dividends were to be declared. However, what was missing in the DGI’s answers was an explanation on how the estate of the bankrupt had been administered over the past 13 years, what actions were initiated in determining the bankrupt’s assets, its creditors, his properties and how much had been realised in the past 13 years. Instead, what surfaced through the case was there was practically minimal effort by the DGI in proactively uncovering any estate, resulting in the creditors hardly recovering any debts.

- The bankrupt did not turn up for meetings. How can the DGI make any inroad if the bankrupt did not avail himself? The DGI did not even make any attempt to locate the bankrupt. How then could the DGI achieve any results and call for a creditors meeting?

- The DGI, in exercising his discretion under Section 33A, alleged that his power was “absolute” by giving the bankrupt a “second chance” as well as reduce the burden of administrations of bankrupts. Any discretion must be exercised in compliance with the provisions of the bankruptcy laws. The DGI should not use and apply the government policy blindly without considering whether the bankrupt deserved a second chance when the bankrupt had failed, neglected and refused to abide by the numerous sections of the laws—by swearing a declaration containing a true and correct statement of his business, assets and liabilities; and submitting to the DGI the Debtor’s Statement of Affairs, and discoveries and realisation of his properties.

- Failure to do so would amount to contempt of Court. Any policy of giving the bankrupt a second chance in life must be considered in light of legal compliance and moral factual matrix. Even in considering parole or a reduction of sentence for a criminal, the Parole Board or the authority empowered to decide, must consider and take into account the individual’s conduct, attitude, actions, respect for the law and prison’s regulations while serving time in prison. It should never be based on a “timeline basis” or simply to reduce the number of prisoners.

- In this case, however, the bankrupt did not show any remorse, did not give a single cent of monetary contribution, did not submit any reports or statements to facilitate administration by the DGI. In short, from day one, he showed sheer utter disrespect and defiance of the bankruptcy laws.

In fact, the DGI, with his lackadaisical attitude, failed to carry out a proper and complete investigation into the affairs of the bankrupt.

As a result, in July, the High Court ruled in favour of the judgment creditor to annul the COD. It was a victory against the injudicious action of the DGI.

7. Recommendations for reform

A more balanced regime could preserve bankrupts’ rehabilitation while respecting creditor interests. We suggest the following reforms:

- Mandatory partial repayment threshold before discharge eligibility.

- Creditor notification and right to object within a prescribed timeframe.

- Judicial or quasi-judicial review of DGI decisions under Section 33A, which definitely are not absolute.

- Public registry of discharged bankrupts, akin to CCRIS (Central Credit Reference Information System) or CTOS (Credit Tip-Off Service) reporting.

These safeguards would align Malaysia’s framework with international best practices and restore the reciprocal fairness necessary for a functional insolvency system.

Conclusion

Section 33A reflects a commendable intent to modernise Malaysia’s insolvency regime and reduce the social stigma of bankruptcy. However, it does so at a significant cost to creditor rights, legal integrity, and the overall health of the credit market. The absence of a repayment obligation or objection process renders the provision open to exploitation, abuse and invites long-term consequences for the country’s credit and legal ecosystems.

Reform is needed to strike a better balance—one that neither traps bankrupts indefinitely nor absolves obligations without accountability.

The new Section 33A may serve the interests of bankrupts, but it does so at the unjust expense of creditors, many of whom suffer equally under the burden of unpaid debts. Justice, in insolvency law, demands fairness on both sides—debtor and creditor alike.

A contract broken by financial hardship is forgiveable—but absolution without restitution is a betrayal of commercial trust, which would have wider repercussions to the whole nation’s reputation and economy if left unchecked.

This article is co-written by Albert KY Soo, National House Buyers’ Association (HBA) legal advisor and lawyer for the Judgement Creditor above; and Datuk Chang Kim Loong, HBA honorary secretary-general.

HBA is a voluntary non-government and not-for-profit organisation manned wholly by volunteers.

HBA can be contacted at:

Email: [email protected]

Website: www.hba.org.my

Tel: +6012 334 5676

The views expressed are the writers’ and do not necessarily reflect EdgeProp’s.

As Penang girds itself towards the last lap of its Penang2030 vision, check out how the residential segment is keeping pace in EdgeProp’s special report: PENANG Investing Towards 2030.