- One thing the Klang Valley has plenty of is shopping malls—from mega to mini, and more in between. What does the data say about their sustainability in relation to how big or small they are?

What are the key factors to ensure a shopping mall’s success? Typical answers often include strategic location with good accessibility, positioning of the mall, a compelling tenant mix and anchor stores, and creating a positive customer experience through amenities, entertainment, and marketing. On top of that, adaptability to new trends like e-commerce integration and experiential retail, as well as superior maintenance, operational efficiency, and proactive management are also crucial to long-term success.

Yes, all the above factors are essential to the sustainable development of shopping malls, but what is often taken for granted is the size. Physical size does play a crucial role as it is a fundamental and initial parameter for the development of shopping malls. It not only determines the layout and the placement of anchor stores or retail outlets to create a desirable and fully functional environment that attracts foot traffic, but also directly affects the types of stores, the combination of facilities, customer convenience, and the overall appeal of the mall, especially from the outset of mall development.

Determining the right mall size involves a strategic balance between maximising potential visitor numbers and a diverse tenant mix, while ensuring a comfortable and accessible environment for shoppers. Larger malls can house more retailers, including strong and major tenants. This gives the mall a competitive advantage in attracting shoppers from a greater catchment area. Besides, a larger mall size is directly linked to the number of facilities it can provide, which in turn facilitates a more pleasant environment that lures more shoppers.

Shoppers are often drawn to larger malls because of the greater variety of goods and the availability of numerous options for dining and entertainment.

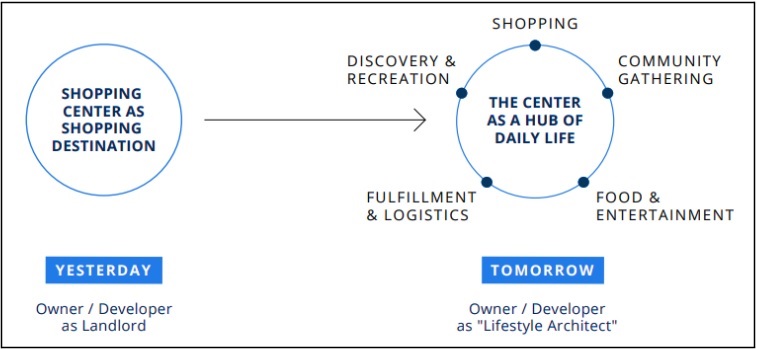

Owing to the structural changes in technology, socio-demography, and consumer shopping habits, the role played by shopping malls has evolved over the years, turning from a symbol of pure consumerism and go-to shopping hubs for urban and suburban societies into lifestyle centres that provide shopping and entertainment, as shown in Figure 2. Although the findings are derived from a North American-based company in 2020, they are congruent with the current pattern in Malaysia. In the author's conversations with some shopping mall experts, all of them agree that in order to encourage extended visits and draw larger footfalls, local shopping malls are shifting from departmental stores selling necessities into entertainment hubs, where people gather, rest, and hang out with peers.

Correspondingly, larger spaces are needed to provide one-stop convenience that can accommodate a diverse set of services to meet the commercial, entertainment, cultural, educational, and social purposes. Destination malls, which are large shopping centres designed for consumers from both the local area and beyond, can leverage their large spaces to create all-in-one experiential hubs that online shopping cannot replicate. Hence, destination malls are said to exhibit greater resilience to the pressure of e-commerce.

Smaller malls, on the other hand, often struggle to attract strong retailers or tenants, as they lack space to house a wide variety of shops and services, wider walkways, better signage, more comfortable rest areas, green spaces, and even more entertainment options that can contribute to a better customer experience. This makes them less appealing for a broad customer base seeking a complete shopping, dining, and entertainment experience, which in turn impacts the mall's long-term survival.

More importantly, with their more conventional offerings, smaller malls are in direct competition with the core strengths of e-commerce: convenience, product variety, and lower pricing. Coupled with limited resources and technical expertise to develop a strong online presence, smaller malls often struggle to adapt to rapidly changing consumer preferences. Hence, the surge in e-commerce is said to have a more profound impact on smaller malls.

While smaller malls are generally at a disadvantage in terms of variety of goods and entertainment amenities, they can perform well if they leverage their strong community connections, much like local-based malls that offer everyday essentials and local specialty shops, providing convenient shopping and interaction venues for immediate local residents in underserved secondary towns.

This necessity-driven positioning has greatly supported resilient footfall and occupancy rates for local-based malls, especially during pandemic lockdowns, when shoppers generally prioritised quick and need-based shopping trips near home because of travel restrictions and health concerns. Unlike destination malls that heavily rely on international and interstate visitor traffic, travel restrictions and border closures have effectively cut off the wide range of customers that destination malls typically serve.

However, as people “go back to normal”, their shopping behaviour has returned to the pre-pandemic days too, with the retention of certain pandemic-induced digital and cautious behaviours like continued online adoption, and more value and authenticity-driven decisions. In the “new normal,” people’s shopping behaviour is a hybrid of old and new habits, characterised by a continued reliance on e-commerce for convenience and price comparison, combined with a renewed desire for the in-store physical experience and immediate product interaction.

As malls begin to resume as multi-functional destinations offering a seamless experience to meet today’s diverse needs for an integrated “live-work-play” environment; a decent mall size to support extended visits is crucial, especially in a regional market like the Klang Valley, where mall cannibalisation remains a concern. Since new malls continue to be built despite existing competition for the same limited pool of shoppers, smaller malls, especially those that are old and less innovative, are easily "cannibalised" by larger and more attractive competitors.

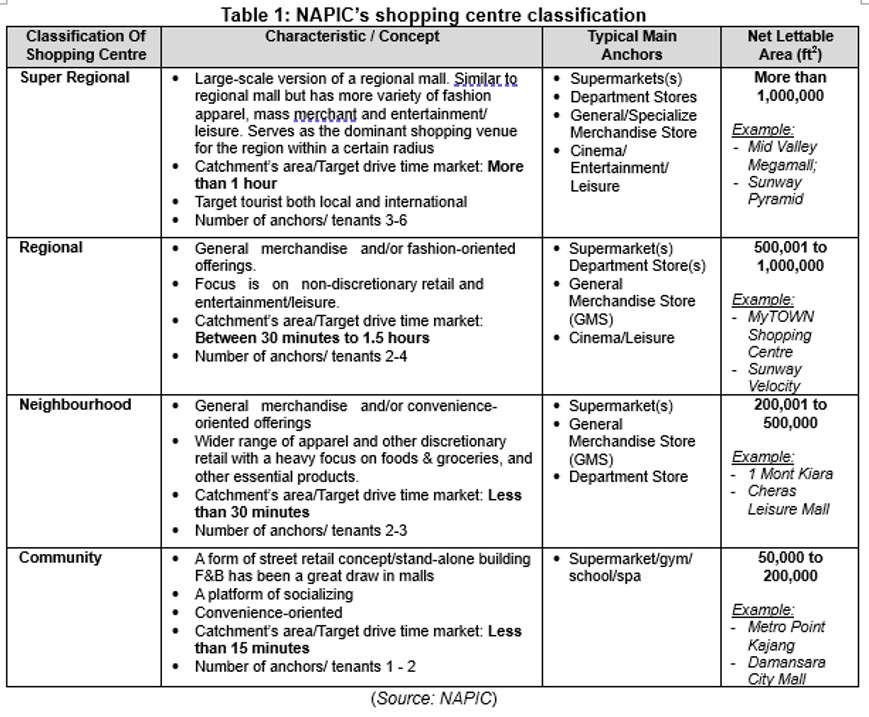

By studying the supply and demand of retail space in four common types of shopping malls in the Klang Valley, namely: super-regional mall, regional mall, neighbourhood mall, and community mall (refer Table below), one can observe how shopping malls of different sizes can withstand the risk of recession.

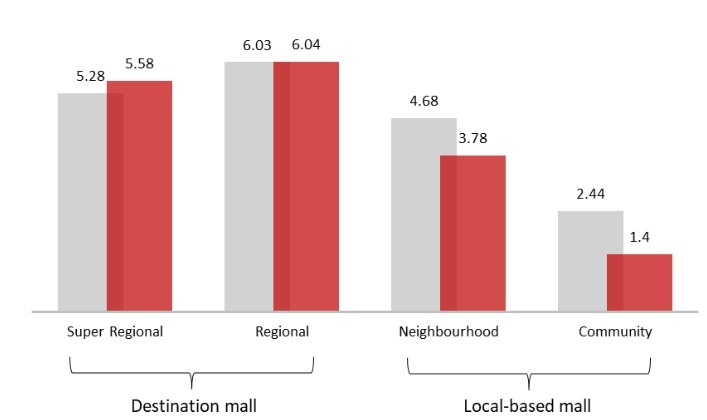

Throughout 2010–2023, there is a clear sign of oversupply of local-based malls, with the demand rate for retail space in both the neighbourhood and community malls growing at 3.78% and 1.4% respectively, falling below the supply rate at 4.68% and 2.44% respectively. In contrast, the demand rate for retail space in super-regional and regional malls grew at 5.58% and 6.04% respectively, which was slightly higher than the supply rate at 5.28% and 6.03% respectively; indicating a balanced growth of destination malls in the Klang Valley region (Figure 3).

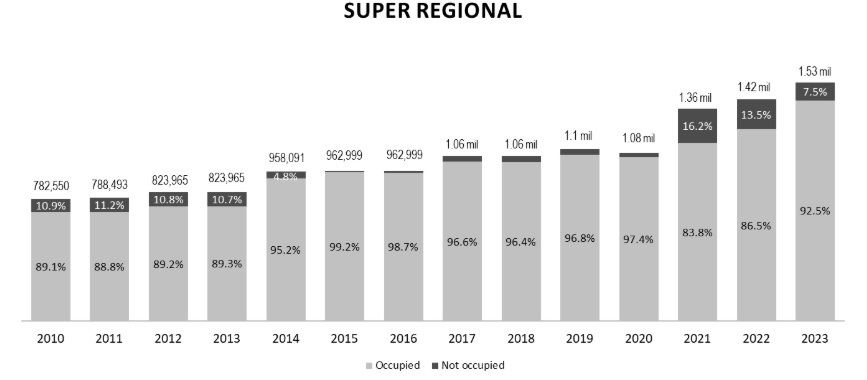

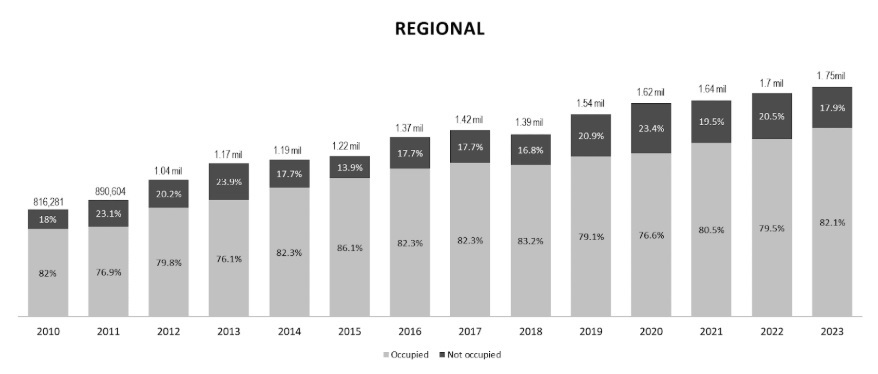

Both super-regional and regional malls have demonstrated resilience in the face of economic uncertainty. Mostly sited in prime locations, these malls have maintained relatively high occupancy rates, ranging between 82% and 92% throughout 2010–2023. Although the occupancy rate of super-regional malls in 2023 (92.5%) was lower than the peak occupancy rate in 2015 (99.2%), it was still higher than the level recorded in 2010 (89.1%) (Figure 4). Moreover, by total NLA, 2023 recorded a higher total occupied space of 1.53 million sq ft compared to 962,999 sq ft in 2015.

As for regional malls, the occupancy rate in 2023 (82.1%) was also lower than the peak occupancy rate in 2015 (86.1%), but it was not below the level recorded in 2010 (82%) (Figure 5). Again, by total NLA, the total occupied space in 2023 at 1.75 million sq ft surpassed that of 2010 at 1.22 million sq ft.

Unlike destination malls, which are better equipped to adapt and attract visitors because of their unique offerings, size, and entertainment options, local-based malls that focus on traditional retail model and convenience-driven shopping are more likely to become obsolete as their limited sizes have inhibited them from future expansions, and thus restricting them from meeting the changing customer needs. Notably, oversupply of local-based malls is becoming more significant as the market is saturated with retail space offerings following a sharp increase in the number of serviced apartments and mixed-use developments over the past decade, leading to an intense competitive pressure towards smaller shopping hubs.

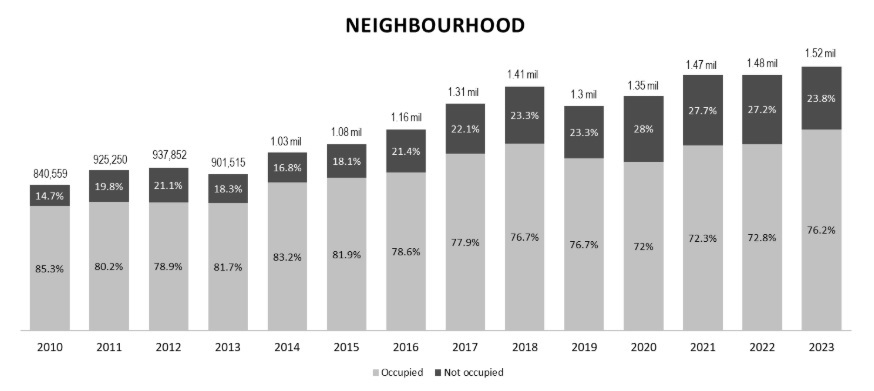

Throughout 2010–2023, the total occupied space of neighbourhood malls steadily increased, but the occupancy rates declined from the highest rate at 85.3% in 2010 to 76.2% in 2023 (Figure 6), indicating a slowdown in demand growth during this period. Although Malaysia currently lacks a unified standard to define whether a shopping mall's occupancy rate constitutes a "struggling mall" or a "dead mall", an occupancy rate below 70% is often deemed as an indication that a shopping mall's financial situation is precarious, and an urgent revival effort is needed.

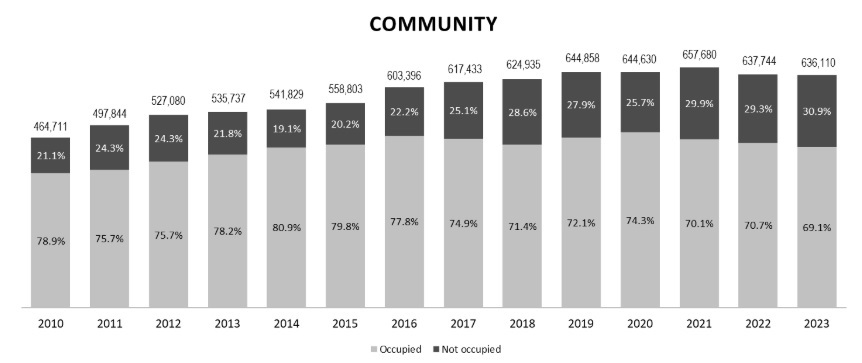

The situation is even more dire for community malls. Not only has the occupancy rates declined from 78.9% in 2010 to 69.1% in 2023, but the total supply area is also continuously decreasing. In 2023, the total space supplied was recorded at 636,110 sq ft, falling back to the level of 2018–2019; while the actual space occupied was recorded at 439,666 sq ft, falling back to the level of 2014–2015 (Figure 7).

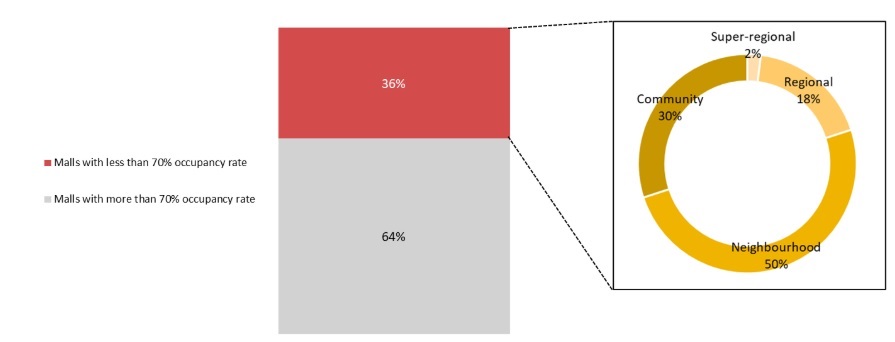

Through the author’s survey on the occupancy rate of 86 malls in the Klang Valley (out of 148 malls as reported by Napic in 2023), 36% of the malls surveyed are considered “struggling malls” with occupancy rates lower than 70%. As high as 80% of these “struggling malls” are contributed by local-based malls, in which 50% are neighbourhood malls while the remaining 30% are community malls (Figure 8). Combined with the above Napic’s statistics, one can conclude that destination malls are more resilient to competitive pressures in the long run and are therefore more robust in today's rapidly changing retail environment.

Having said that, regardless of size, shopping malls remain vulnerable to market changes if they lack the willingness to continuously adapt to evolving consumer preferences. This includes adopting new retail technologies (such as mobile apps and interactive displays), reconfiguring physical spaces for greater flexibility, and employing omnichannel strategies that seamlessly integrate online and offline shopping. Although physical size forms the basic framework and determines initial strategic choices, effective management is crucial for navigating a rapidly changing market, maximising potential, and improving performance. Ultimately, only those shopping malls that can better adapt to market changes and attract customers through their unique merchandise, scale, and entertainment options will stand out.

Foo Chee Hung holds a PhD in Urban Engineering, and is the principal researcher of MKH Bhd.

The views expressed are the writer’s and do not necessarily reflect EdgeProp’s.

Unlock Malaysia’s shifting industrial map. Track where new housing is emerging as talents converge around I4.0 industrial parks across Peninsular Malaysia. Download the Industrial Special Report now.